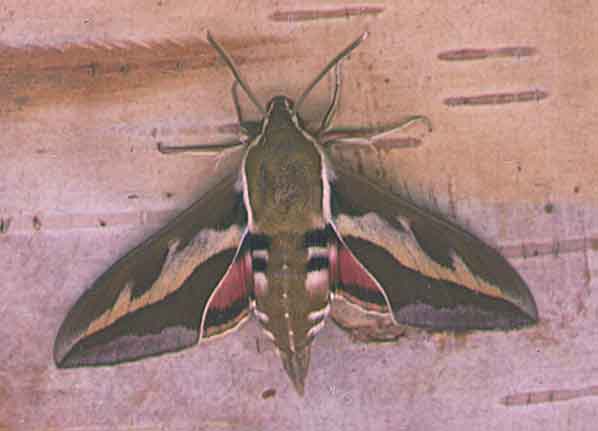

Hyles gallii scan by Bill Oehlke.

This site has been created by Bill Oehlke.

Comments, suggestions and/or additional information/sightings are welcomed by Bill.

TAXONOMY:Family: Sphingidae |

This site has been created by Bill Oehlke.

Comments, suggestions and/or additional information/sightings are welcomed by Bill.

TAXONOMY:Family: Sphingidae |

The forewing is dark brown with a slightly irregular cream-coloured transverse line. The outer margin is grey. There is a bright pink band on the hindwing.

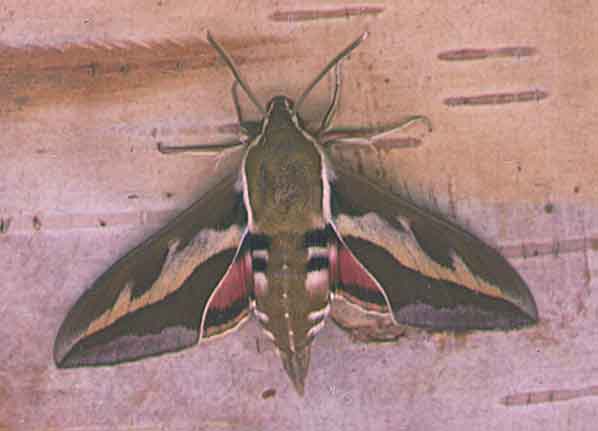

Hyles gallii, June 16, 2005, Peterborough, Ontario, courtesy of Tim Dyson.

Hyles gallii ranges coast to coast in Canada (into the Yukon) and southward along the Rocky Mountains into Mexico. It is also widely distributed throughout Europe and Asia.

Ken Philip reports it in Alaska from early June until mid July in the Haines Region and also in Ivotuk Hills near Otuk Creek on the North Slope.

Visit Hyles gallii in flight, Old Newark Valley Road, Endicott, Broome County, New York, July 31-early August, Paula Carman.

The following night she laid approximately twenty, extremely small, glossy, greenish-blue eggs, and added about fifteen more on July 8. She did not lay any eggs on July 9 and seemed to lack energy so I decided to feed her.

I mixed up a small solution of 1 tsp white sugar, 30 ml warm water, and 1/4 tsp honey. After thorough mixing and allowing the mix to stand until it cooled to room temperature, I poured some of the solution into a small jar cap. I gently removed the female from the bag and held her thorax at the base of her upward-folded wings between the thumb and forefinger of my left hand. I allowed her legs to rest on the rim of the jar cap and inserted a pin through the proboscis coil under her head. I carefully extended the proboscis (approximately 35mm) into the solution. At one point I removed the pin and she recoiled her proboscis, but then extended it again on her own into the solution. After about five minutes of feeding I placed her in another bag.

Normally I obtain eggs from female Saturniidae and Sphingidae, by simply placing them in fresh paper bags every two days and moving the eggs on paper clippings to emerging jars. Since I was going to be away for an extended period of time starting on July 9, I had to make alternate arrangements.

I had several small patches of Epilobium angustifolium, one of the larval food plants of Hyles gallii, growing in my yard, so I used a garbage bag twist tie to fasten two closely growing stems together about 8 inches from the ground. The plants were about 3.5 feet tall at this time. I used a Remay sleeve (height 4 feet, diameter 1.2 feet) with two open ends to enclose the Epilobium. The bottom was tied shut around the stems at the twist tie level with a piece of cotton string. I used some thin strips of masking tape to tape paper-egg strips to the epilobium leaf stems and then inserted the female into the sleeve. I closed the top of the sleeve by bringing four equidistant points to a center and then folding down the gathered cloth in two half inch folds which were secured with two clothespins. The weed stems, which were in a semi-sheltered, semi-shaded spot, were sturdy enough to support the sleeve and clothespins.

Photo courtesy of Dave Prentice, the BC Adventure Network |

Epilobium angustifolium is commonly known as fireweed because it often grows in burnt over locales. It often gets established in disturbed sites. It prefers full sun, but does okay in partial shade.The perennial plant grows from two to nine feet tall with narrow leaves growing up to 8 inches long. Reproduction is from seed and rhizomes. Often an entire burnt over field will begin its regeneration with an expanse of fireweed. In the wild females normally lay 4-5 eggs on the leaves of each host plant.

When eggs are deposited on Galium, the female will sometimes

lay them on the flowers. |

Photo courtesy of Dave Prentice, the BC Adventure Network |

When I returned home from my trip on July 19, I checked the sleeve. There were many small green larvae of varying sizes, several slightly larger black ones, and a bit of food left.There is considerable variation in larval colouration and markings. Some larvae hold the green colour into final instar while most have turned black by the second instar. |

|

I quickly set up four more rearing sleeves with double stems in each and moved all 95 larvae the following day, putting approximately twenty four to a sleeve. These larvae were not very "clingy" and I had to be careful moving them. With the slightest disturbance, they would let go of their leaf/stem hold and fall to the bottom of the sleeve. Even as they grew larger, they would tend to fall from leaves and stems when disturbed.

Larvae, which were smooth, shiny, and predominantly black, grew extremely rapidly.They reminded me of warm, black licorice strips in that they were shiny, long and thin, and did not seem to have or exercise much longitudinal muscle strength. Scan by Bill Oehlke. |  |

I moved most of these hornworm larvae indoors as they moved into their fifth instar in about four weeks. It was far easier to gather cut food from nearby sources and put five to six stems into five gallon containers with ten-twelve larvae/container than it was to be constantly shifting outdoor sleeves.

Droppings and frass were removed from the buckets at least every other day. These larvae have relatively small heads so buckets had to be kept tightly closed. Most of the larvae left the food plant stems and began circling the bottom of the bucket at pupation time.

I moved these larvae to similar buckets that had several layers of loosely settled paper towels in the bottom. The larvae crawled under the upper layers and spun very flimsy cocoons, just a few strands of silk to hold the towelling in place. A few larvae spun similar "cocoons" in leaf wraps near the base of stems. Most larvae had pupated within four days of moving to pupation buckets. The pupae were a tan color with some dark brown speckling.

Eight out of ninety pupae emerged within four weeks; the others went into winter diapause and were put into cold storage in a loosely lidded container ( I now use closed ziploc containers) in the refrigerator crisper. I also put some damp peat moss in another loosely lidded container in the crisper to retain high humidity.Scan to right by Bill Oehlke. |  |

Once a month, pupae received a cold water bath (water chilled in crisper) which consisted of dunking them for about two seconds into a bowl of water and then letting them air dry on some paper towelling before going back into storage. The bath is to stimulate natural "rainy" conditions and to prevent desiccation of naked pupae.

Storage in an airtight ziploc plastic container with two drips of water on some paper towelling eliminates the need for the monthly bath. I have often looked for gallii larvae (black with small red heads and a red horn in fifth instar) on epilobium, but have never found them. In the later instars, this species is predominantly a night time feeder and descends the plant stem to hide in the day. Larvae progressed extremely rapidly indoors and this may have been due to the dark conditions in the tightly lidded buckets as well as the warmer indoor temperatures.

In late June of 2000 I captured two females at lights and they deposited large numbers (100 +) of eggs in paper bags without any feeding.

by Bill Oehlke

There is also a brown larval form. Jim Tuttle suspects there may also be a green form although he hasn't seen one yet.

It is interesting to me that Colleen Wolpert has reported Hyles gallii, in Apalachin, Tioga County, New York, on August 15, 2010, and on June 4, 2011.

I suspect the mid August 2010 sighting was an attempt at a partial second brood. Perhaps larvae would be able to mature before cold weather set in, but it would probably require a warm late summer, early fall.

C. G. Morton reports larvae on northern willow herb, (Epilobium glandulosum), in Rawlins, Carbon County, Wyoming.

Ian Miller reports he is rearing larvae on evening primrose inside the butterfly house in Wisconsin.

Joe Garris from Sussex County, New Jersey, writes, "I've reared a few (8) H gallii from ova that Tony McBride gave me [from Warren County]. The eggs hatched, all by 6/6/18, pupated by 7/1/18 and were all out by 7/18/18."

Hyles gallii fifth instar, Edmonton, Alberta,

July 2006,

courtesy of Joanne Bovee, via Robert Bercha, id by Bill Oehlke, confirmed by Jim Tuttle.

Hyles gallii fifth instar on fireweed, Edmonton, Alberta,

July 20, 2018,

courtesy of Sue Panteluk id by Bill Oehlke.

Hyles gallii, fifth instar, Saratoga National Historical Park, Saratoga County, NewYork,

parasitized, September 26, 2010, courtesy of Matt Pelikan.

Hyles gallii fifth instar, Pt. MacKenzie, Alaska,

September 24, 2012, courtesy of Dave Helgert.

Hyles gallii pupa, Lyndonville, Caledonia County, Vermont,

40mm in length, courtesy of Don Miller, tentative id by Bill Oehlke.

Hyles gallii pupa, Lyndonville, Caledonia County, Vermont,

40mm in length, courtesy of Don Miller, tentative id by Bill Oehlke.

Visit Hyles gallii, fifth instar, Sibbald Flats, Kananaskis Co., Alberta, August 31, 2011, Betty Ann Swaim.

Visit Hyles gallii larva, near Wasilla, Alaska; 61d37m north, 149d23m49s west; feeding on fireweed;

September 18, 2011;

Carl Seutter

Visit Hyles gallii larva, Anchorage, Alaska; 61° 8'10.09"N Latitude and 149°46'27.07"W; September 24, 2011; Joel Adams

Visit Hyles gallii, larva, Anchorage, Alaska, August 7, 2013, Ted Haussner.

Visit Hyles gallii adult, Athol, Worcester County, Massachusetts, June 19, 2011, Betsy Higgins

Visit Hyles gallii, larva, Prince William Sound, Esther Island, Alaska, August 15, 2013, Kristin Beck.

Visit Hyles gallii, Shrine of St. Therese, Juneau, Alaska, August 7, 2013, Laurie Lamm.

Visit Hyles gallii, larva, Soldotna, Alaska, October 4, 2018, Bryr Harris.

One of the best sites to visit for information and pictures of Sphingidae

is

Tony Pittaway's "Sphingidae of the Western Paleartic"

Use your browser "Back" button to return to the previous page.

Goto Main Sphingidae Index

Goto Macroglossini Tribe

Goto Central American Indices

Goto Carribean Islands

Goto South American Indices

Goto U.S.A. tables

Enjoy some of nature's wonderments, giant silk moth cocoons. These cocoons are for sale winter and fall. Beautiful Saturniidae moths will emerge the following spring and summer. Read Actias luna rearing article. Additional online help available.

Eggs of many North American species are offered during the spring and summer. Occasionally summer Actias luna and summer Antheraea polyphemus cocoons are available. Shipping to US destinations is done from with in the US.

Use your browser "Back" button to return to the previous page.

This page is brought to you by Bill Oehlke and the WLSS. Pages are on space rented from Bizland. If you would like to become a "Patron of the Sphingidae Site", contact Bill.

Please send sightings/images to Bill. I will do my best to respond to requests for identification help.

Show appreciation for this site by clicking on flashing butterfly to the left. The link will take you to a page with links to many insect sites. |